Decline of natural habitat

Wetlands and intertidal flats are valuable habitats and essential for coastal protection as well as livelihoods. Together, the combination of large areas with shallow waters, tidal flats, mangroves and unregulated rivers effectively mitigate impacts from tidal, typhoon, and river flooding. According to the International Guidelines on Natural and Nature-Based Features for Flood Risk Management, [19] wetlands, including intertidal flats, can deliver benefits in the following five ways:

-

Reducing long-term shoreline erosion, which exacerbates future flood risk;

-

Trapping and stabilizing coastal sediments, which contributes to coastal wetland surface elevation and land build-up, and consequently reduce future flood risk;

-

Weakening the energy of a storm surge, and hence the height, of incoming waves, which reduces the total water levels, or the wave energy transmitted to habitats or structures landward of the wetland;

-

Providing flood storage, which redistributes the total flood volume, thereby reducing flood damages in adjacent areas.

The North Manila Bay delta used to have large mangrove areas; its natural stage had more than 80,000 ha [18]. Mangroves are among the most productive ecosystems, and they provide a nursery function to various species of fish and other marine life and breeding places for waterbirds. Mangroves are also effective carbon sinks; they absorb carbon dioxide and convert it to oxygen through photosynthesis.

The natural habitat made up of mangroves, and tidal flats capture the sediments coming from the rivers upstream, allowing it to grow together with any water level changes. With the natural habitat gone, the ability of the North Manila Bay to grow (to a certain extent) with rising sea levels and subsiding grounds is substantially reduced.

The original wetlands in the North Manila Bay Delta cover about 80,000 hectares. Within the 2-meter water column [16] they provide food and habitat for fish, waterbirds, and other wildlife, maintaining and improving the water quality of rivers, lakes, and estuaries, acting as a reservoir for watersheds, and protecting properties from potential flood damage. While there has been a very significant decline over time, the remaining tidal flats and shallow areas remain essential habitats for fish and benthic life forms necessary for livelihoods and for threatened migratory waterbird species and the functioning of the Manila Bay ecosystem.

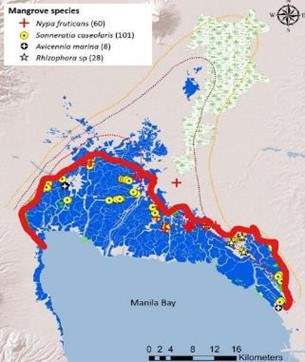

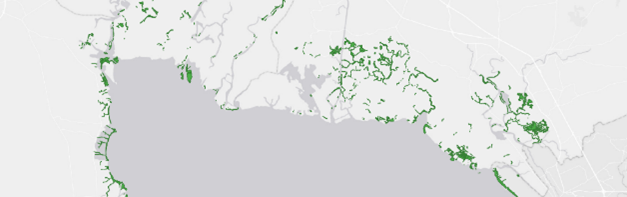

The decline of the mangroves in North Manila Bay Delta is best described by the figure above. Rollon et al. [18] did research into the distribution of mangrove species. Together with other spatial data, it can be concluded that the "old" coastline, the current saltwater hightide where fragments of mangroves still are present, can be indicated by the red line in the figure above. This means that about 70,000 hectares of mangroves have disappeared since the cultivation of the North Manila Bay Delta. There are few locations left with mangroves, as shown in the figure below.

The figure above also indicates that the coastline (with a definition where the land meets high tide, hence where the historic mangrove presence would stop) has been pushed outwards by cultivating the mangrove and wetland areas into fishponds [20]. This subsequently means that the people living in these tidal exposed areas are vulnerable to flooding. Further construction of fishponds and dikes only worsens this situation.

Coastal mangrove forest in Bulacan Photo: Arne Jensen (left) Christina Cinco (right)

The figures above shows some impressions of the remaining mangroves and coastal forest in the North Manila Bay delta. Besides the decline in mangrove areas, the mudflat areas have been replaced (mainly) by fishponds combined with conversion into mangrove plantations. Tidal mudflats are of huge environmental significance. They provide a food source for local people and are crucial feeding areas for migratory waterbirds, offer protection against incoming waves, and help tackle climate change by absorbing great carbon dioxide levels.

Tidal mudflat in Bulacan (Left) and sample of high-density mollusc bivalves in mudflats (right) Photo: Arne Jensen

Shallow waters with congregations of threatened migratory waterbirds in Bulacan and livelihood fishing area. Photos: Diuvs de Jesus (left) Jasmine Meren (right)

It can be concluded that 99% of the mangrove forest and about 80% of all tidal flats have been removed and converted into fishponds within a century. Next to that, all major rivers became regulated, impacting the sediment dispersion within said mangrove forest and tidal flats. Due to this, the coast North Manila Bay Delta is less protected against surges and wave attack, and the area has a negative sediment balance (due to less input and less sediment capture), which increases the problem due to erosion of the coastline.

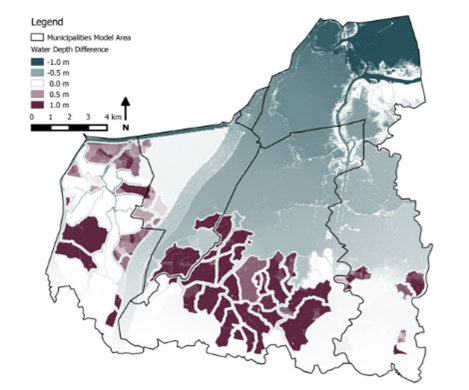

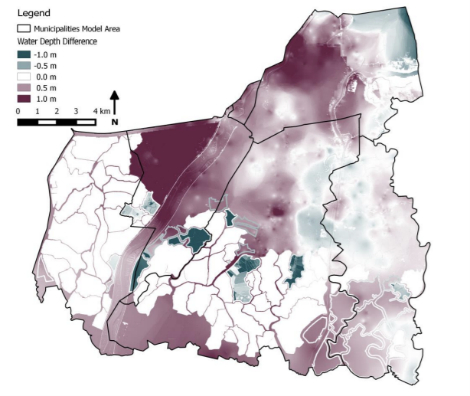

A thesis study by ‘t Veldt [21] shows that the presence of the fishponds on the historic tidal planes causes flooding upstream. This is best illustrated by the figures below, which shows numerical flood modelling results for 50-year subsidence/flooding scenarios. It was assumed that the fishponds will remain operational and “diked” for one scenario. It was assumed that the fishponds would be abandoned over time for the second scenario.

Fluvial flood scenarios 50 years [21] including subsidence; left “abandoned fishponds”; right with fishponds maintained